A systems approach offering intensive care for the most at-risk students and specialized attention for those with moderate literacy needs.

Originally published in AASA’s The School Administrator, April 2006 Number 4, Vol. 63

Middle schools and high schools across the country face a literacy crisis of monumental proportions. Whether they are students from households where English is a second language or learning-disabled students mainstreamed into difficult classes, struggling readers demonstrate lower achievement in all academic subjects. While many poor readers have developed coping strategies, they rarely improve their academic performance or test scores.

Secondary schools are ill-equipped to help these students become better readers. And with a more diverse student population entering middle and high school than ever before, the challenge of educating under-prepared readers will only increase. Whether the problem stems from societal change, the use of instructional reading practices in elementary school lacking research support or some combination of factors, these struggling readers deserve to learn. And they can’t learn if they can’t read. Understandably, secondary school students who are reading below grade level often are unmotivated and turned off to reading. Many of them are the same students who were poor readers in 3rd grade — about 75 percent of students with reading problems in 3rd grade will still have them when they get to high school, according to Sally Shaywitz, professor of pediatrics and child study at Yale University School of Medicine. In fact, research shows that the gap between good and poor readers actually widens in later grades.

Besides poor academic achievement, these students frequently suffer emotional and psychological consequences from their reading problems, including anxiety and low self-esteem. Ambitious curriculum standards and widespread use of assessments make academic life more stressful for underachieving readers and the middle and high schools’ task all the more challenging.

A Workable System

To improve achievement for struggling readers in particular, secondary schools must design programs and curricula to address students’ lack of background knowledge, delayed English language development and limited success in reading. The best approach is a systems approach, which sets high expectations for all students and includes specialized, intensive interventions for under-prepared students.

The model that CORE, Inc. has developed and successfully implemented is an “educational triage,” with well-run intensive care units for the most at-risk students, specialized care for those moderately at-risk and excellent core instruction for capable readers. In our model, school systems help all teachers effectively teach an increasingly diverse population.

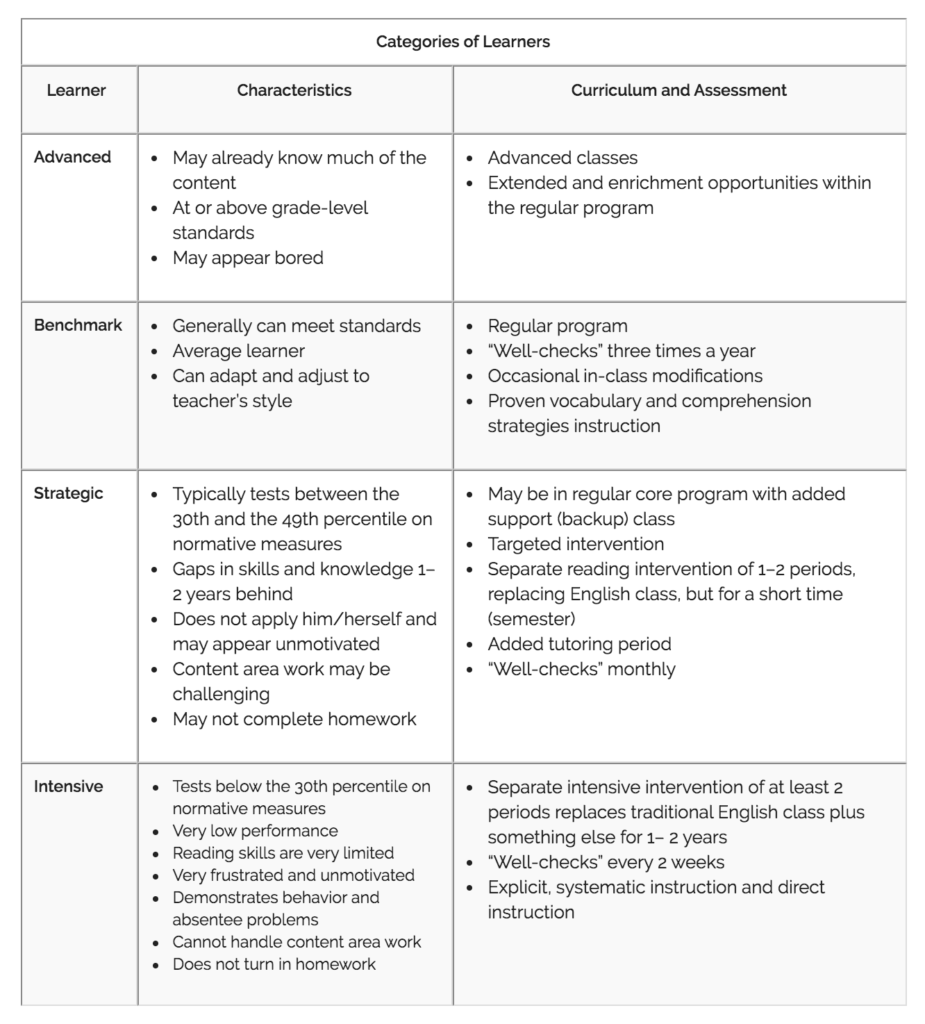

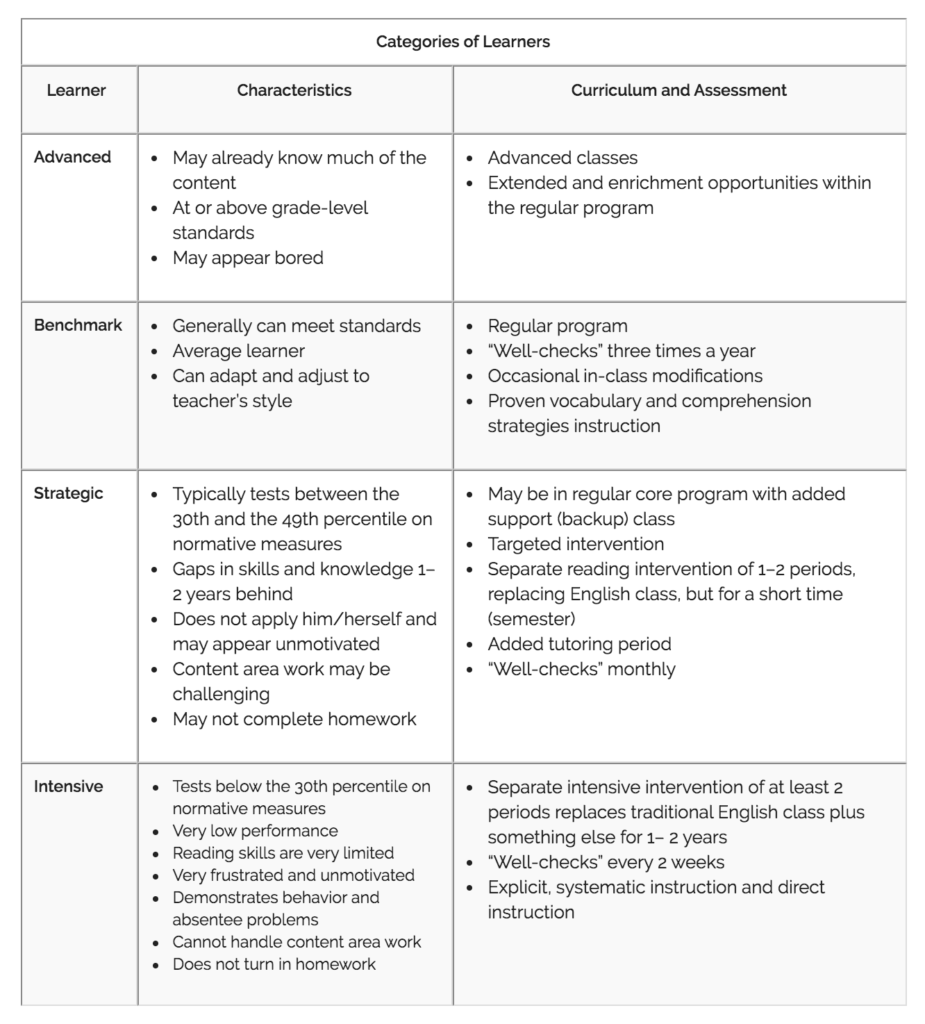

To establish an effective reading plan, it is useful to create four categories of learners with different levels of curriculum, instruction, intensity and duration, according to Edward J. Kame’enui and Deborah C. Simmons in What Reading Research Tells Us About Children with Diverse Learning Needs: Bases and Basics. The table below summarizes these learners, their characteristics, and their curriculum options.

Most secondary schools currently are designed to meet only the needs of benchmark, or average learners, with a few honors classes thrown in for advanced learners (those working at or above grade level standards). Only students formally identified as qualifying for special education receive specialized help.

To meet the needs of struggling readers, schools must rethink their organization, schedules, curriculum materials, programs and teacher training. Intensive learners, or very low-performing students with limited reading skills, will need a specialized classroom of literacy development that is longer and of sufficient intensity and duration to lift them to basic literacy within two years. Strategic learners, or students who are between one and two years behind and typically test between the 30th and 49th percentiles on normative measures, will benefit from an added support class period to enhance their core English classes and fill in skills gaps.

Secondary schools also must equip all teachers with knowledge of effective research-based strategies to help all students in every content area develop reading fluency, improve their vocabulary knowledge and strengthen text comprehension.

Model Program

The successes of Chipman Middle School in Alameda, Calif., illustrate how a carefully planned, multipronged approach to literacy instruction can significantly increase the skill level of struggling readers.

A key component of Chipman’s model included identifying students in three of the categories listed in the chart: Benchmark, Strategic and Intensive. To move to a three-tiered model, Principal Laurie McLachlan-Fry directed a complete restructuring of the school program and the adoption of a core curriculum and intensive programs with student placement based on diagnostic assessment.

The school redesigned its master schedule to accommodate specialized instruction for the intensive learners — three periods using a commercial curriculum with a solid research base and proven track record of increasing student reading skills and test scores. Other students received added support in strategic classrooms with a core English program. A carefully selected team of administrators and teachers received initial professional development and ongoing coaching.

McLachlan-Fry spearheaded the effort with support from her district’s director of curriculum and instruction, Barbara Lee. She held regular meetings with her literacy leadership team, expected all teachers to buy in and built in lots of mentoring and support. McLachlan-Fry also fully participated in data analysis and study sessions to review results of intervention program tests and other assessment data, and regularly observed classroom instruction.

The percentage of Chipman students reading below grade level dropped from nearly 50 percent to 38 percent over two school years. Given the success of this model, the school district has begun implementing it for all schools serving students in grades 6-12. Chipman was recognized for its reading achievement by First Lady Barbara Bush, who visited the school last June.

Necessary Components

The most effective reading intervention programs have the following systemic components:

- adequate training for all teachers expected to teach the programs;

- teacher coaching and ongoing classroom support;

- knowledgeable leaders able to monitor and support instruction;

- appropriate student placement and scheduling with student-teacher ratios and time blocks that adhere to program guidelines;

- appropriate progress monitoring and diagnostic assessments; and

- regular time to analyze student assessment data and plan immediate interventions to address both student needs and teacher support needs.

The Pasadena, Calif., Unified School District created a literacy program based on all of these components. Under the leadership of a new superintendent, Percy Clark, and Deputy Superintendent Kathleen Duba, with support from central administrators who led the literacy team, the district completely restructured services for their middle and high school literacy program.

Working with the Stupski Foundation to adopt a districtwide literacy plan, the leadership required the implementation of the Holt reading program for all students reading at or slightly below grade level, an added support class for students about two years below grade level and an intensive intervention for those reading well below two grade levels.

Staff developed an assessment plan for placing students, and all teachers expected to teach their new intervention and core programs underwent five days of training before the initial implementation. To follow up, the district held multi-day intensive instructional sessions for teachers working with various reading programs, including Holt Literature, Language!, REACH, Read 180 and, for English learners, High Point.

The central-office leadership created a team of district experts, one for each intervention. The team asked all middle and high schools to use a consistent implementation rubric. Each week they checked data, reviewed progress and had regular team walkthroughs in which key central-office personnel participated, after which they would debrief and plan next steps.

Literacy coaches at each site received additional training in the content and approaches of the various reading programs, as well as in the skills and responsibilities needed to be effective coaches.

Central-office administrators, coaches and site administrators were trained in observation procedures for each reading program. CORE and district experts provided ongoing support — with coaching, demonstration lessons and classroom observations — for each site and for each of the reading programs. In addition, a district literacy coordinator ensured that resources were available systemwide to meet the needs of participating schools.

At the systems level, district administrators, starting with the superintendent, actively and visibly provided direction and support. It was their commitment that led to additional funding for coaching, supplies, professional development and mandated schedule changes for longer reading instruction periods. At the site level, leadership teams of school principals, assistant principals, literacy coaches and English department chairs were expected to participate actively in implementing the plan.

This well-coordinated effort in Pasadena is paying off. This year, the English language arts test scores for students in grades 7-11 increased in every grade. Academic Performance Index results showed Pasadena students improving their performance faster than their peers in Los Angeles County and statewide for the second year in a row. The district’s overall increase in the index was 31 points, outpacing a 19-point gain across the county and a 20-point gain statewide.

Yakima’s Approach

Ongoing professional development is critical for equipping teachers and school leaders with the research-based knowledge they need to design their reading programs, select the right tools, implement effective, active learning and explicit teaching strategies across content areas, and develop support systems.

To be effective, professional development must be multidimensional, accounting for teacher background, school culture and the particular needs of adolescents.

Professional development can occur in traditional workshop settings and seminars, during collegial meetings at the school and within the classroom. Our design for professional development includes theory and research, modeling and demonstrations, structured practice and feedback, coaching and classroom application.

In the Yakima, Wash., Public Schools, all English, reading and intervention teachers participated in specific program-based training as well as “reading academies” focused on phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Leadership teams from each middle and high school site attended CORE Reading Leader Institutes, and coaches attended coaching practice sessions facilitated by CORE experts. Content-area teachers participated in vocabulary and comprehension strategy workshops and classroom coaching provided follow-up to actual workshops.

Teachers continue to meet to rehearse lessons, fine-tune problematic instructional components and receive feedback. Principals and district administrators participate in regular classroom walkthroughs and know their reading programs intimately.

The Yakima School District embarked on a reading intervention program when Benjamin Soria examined student achievement test scores upon becoming superintendent in 2000. In collaboration with CORE, the district began a new reading intervention program in 2002, adding a reading coach to every elementary school. The following year, the district placed a reading coach in every middle school and the next year in every high school.

Recognizing the need to also address writing skills, the school district chose High Point for its comprehensive reading and writing curriculum. CORE consultants trained teachers, coaches and district administrators in using the new curriculum.

In 2005, 60 percent of the school district’s 4th graders were proficient readers, as measured by the Washington Assessment of Student Learning, compared to 45 percent in 2003. Students in 7th grade scoring proficient increased by 32 percent in two years, and 10th graders increased reading proficiency 13 percent in one year.

This is especially significant since 28 percent of the district’s students are transitional bilingual or English language learners. Of the 14,500 students enrolled for the 2005-06 school year, 59 percent are Hispanic, 33 percent white, 3 percent African American, 3 percent Native American and 2 percent Asian.

These impressive gains are directly attributable to the well-planned introduction of a scientifically based reading curriculum at every grade level, extended time for instruction (90 minutes a day in middle schools and 110 minutes a day in high schools) supported by on-site implementation assistance, a coach at every site and a tightly designed assessment and pacing plan.

The school district’s goal is to have all students in all 22 schools reading at or above grade level by 2007.

Enduring Effect

Designing, implementing and sustaining effective reading programs is everybody’s business. It requires well designed and ongoing professional development to equip educators with the knowledge base they need for effective reading instruction, the selection of appropriate tools tightly linked to sound research and, finally, support systems initiated by the local leadership to ensure smooth implementation and enduring effect.

To quote Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire: “Now is the time that we must choose between what is right, and what is easy.”