Blog Post

What Is Structured Literacy? An Introduction

Structured literacy has gained widespread recognition for its effectiveness in supporting students with dyslexia and other reading challenges. However, structured literacy isn’t limited to students who struggle with reading. In fact, it offers benefits to every student, regardless of their reading proficiency. But, an important caveat should be stated here – instruction needs to be differentiated to accommodate the variations in how children come to school prepared to read.

Children enter school with varying degrees of preparedness for reading. Some children enter school needing a lot of support to learn to read, and some children enter school with reading abilities. Assessment to determine children’s needs and focus of instruction will be critical. This important idea about assessment is reflected in the Ladder of Reading and Writing that is linked above and will be restated throughout this blog.

Below, we explore the multifaceted nature of structured literacy, examining its significance, methodologies, and the wide-ranging benefits it provides to learners of all abilities.

What Is Structured Literacy?

Structured literacy is a systematic and explicit approach to teaching oral and written language rooted in the Science of Reading. The components of structured literacy are delivered in a systematic and explicit way—students are taught clearly and concisely and are given many opportunities to practice the skills taught.

At its core, reading and writing are grounded in spoken language, i.e., speech. Without language or the ability to communicate orally, reading and writing would not exist. Writing was developed from human speech only about five thousand years ago, long after humans were able to communicate verbally. This long lag between humans’ ability to communicate orally and the development of writing systems that capture ideas from speech is one of several ways that we know that humans are biologically predisposed to learn to speak but not to read and write. In other words, humans are wired with a language-learning brain but are not wired with a reading brain. Therefore, reading and writing must be taught.

Structured literacy is anchored in the concept that reading rests on language and that there is reciprocity between learning to read and oral language development. High-quality teaching of the five components of reading and also teaching writing supports language development. And the act of reading and writing further develop language. In her book, Speech to Print, Louisa Moats states, “When we teach reading and writing, we are teaching language at one or all of its many layers. Reading, after all, is not a rote exercise in recitation of words but a translation of print to speech to meaning that is mediated by the language center of the brain. Language itself is the substance of instruction” (Moats, 2000, p. 2). This quote captures the essence of structured literacy.

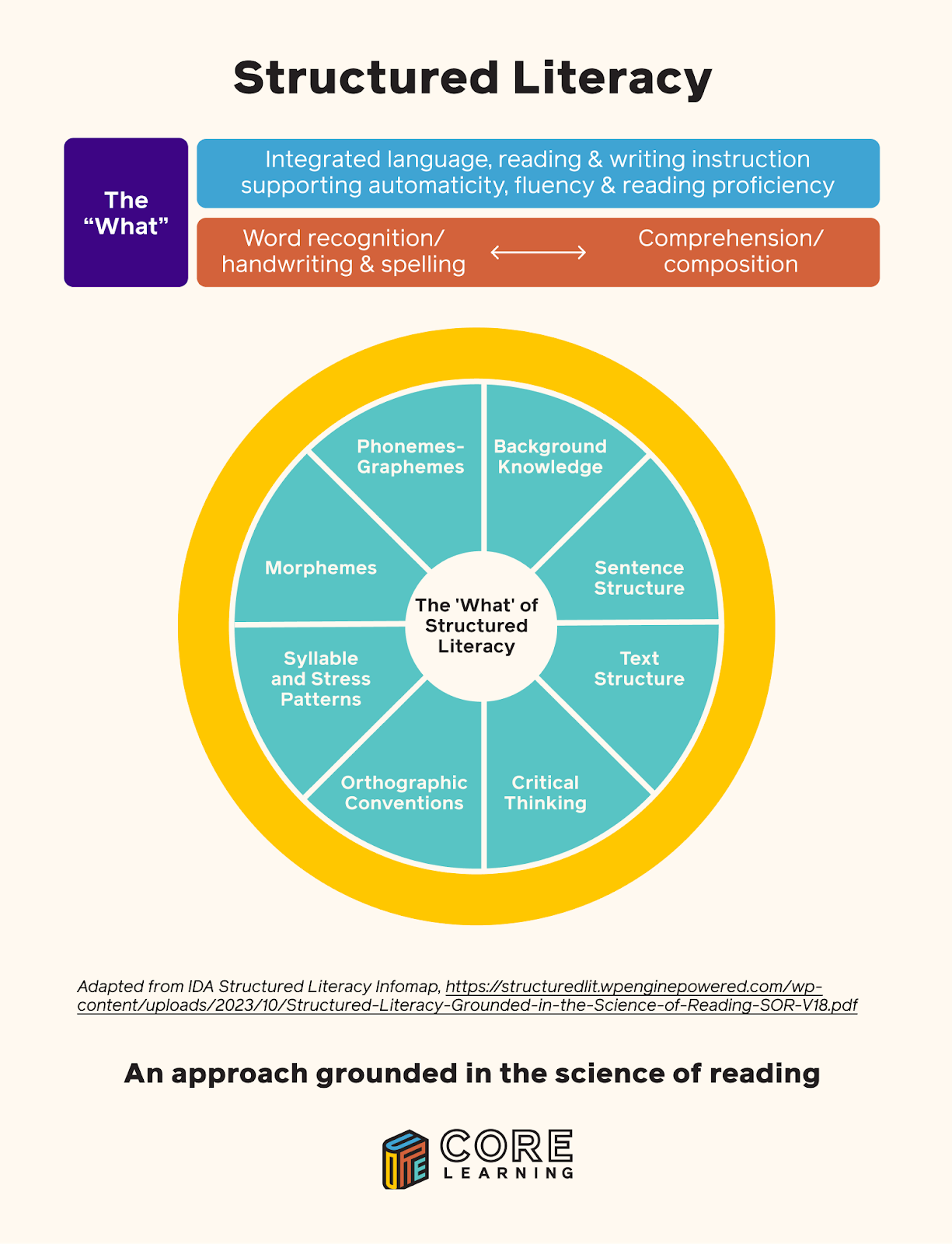

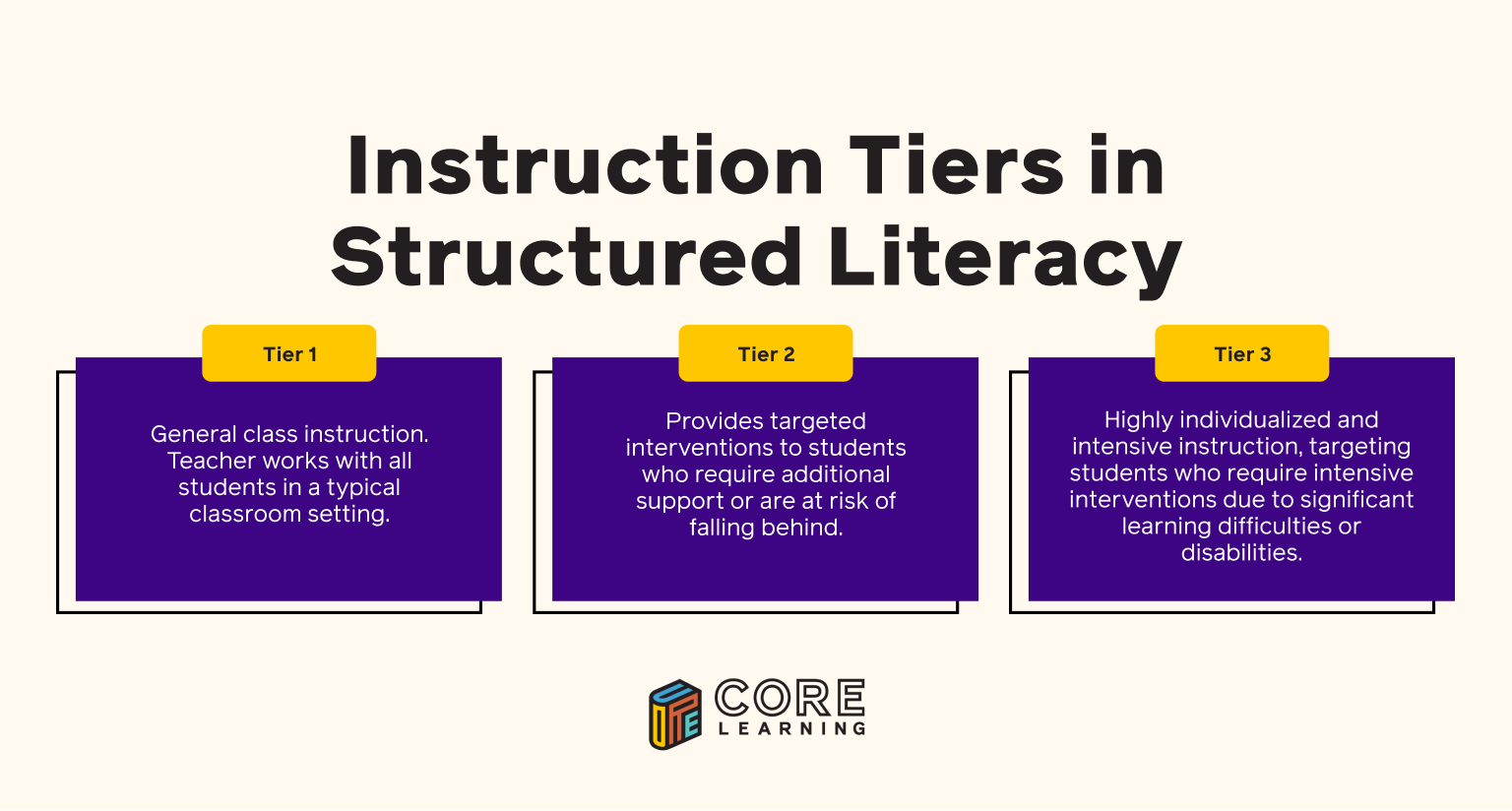

To gain a comprehensive understanding of structured literacy, it’s essential to grasp its dual components: the ‘What’ and ‘How.’ The ‘What’ encompasses the content of instruction. The ‘How’ relates to the methodology employed to deliver that instruction. Put simply, structured literacy addresses both what needs to be taught and how it should be taught. By focusing on both aspects (the what and the how), structured literacy offers a comprehensive and differentiated approach to teaching literacy. This teaching is supported by decades of evidence-based reading research known as the science of reading. It is important to reiterate here that structured literacy is not only for students needing intervention. Structured literacy should be the “modus operandi” for all schools as part of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) which encompasses Tier 1 instruction for all and Tier 2 and 3 interventions for students who need additional support.. Differentiated instruction is key to successful implementation of MTSS..

Is Structured Literacy the Same As The Science of Reading?

Although the terms ‘Structured Literacy’ and ‘The Science of Reading’ may be frequently used interchangeably, they are not exactly the same. The Science of Reading is the extensive body of research that serves as the foundation for structured literacy. Its evidence base informs the components of literacy that should be taught and how those components should be taught. Structured literacy describes the why, the what, the how, and the who, as can be seen in the International Dyslexia’s Structured Literacy Infomap.

In sum, Structured Literacy is the instructional approach firmly rooted in the Science of Reading that identifies how to actualize the instructional content and methods for delivery within an MTSS framework.

The What of Structured Literacy

Structured literacy employs systematic and explicit instruction that integrates listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It addresses all the essential components that are highlighted in the word recognition and language comprehension strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope. These components of Scarborough’s Reading Rope map onto the instructional elements shown in the graphic below that form the ‘What’ of structured literacy:

Phonemes and Graphemes

Phonemes (the smallest units of sound in speech) and graphemes (the letters and letter combinations that spell those sounds). Structured literacy emphasizes explicit and systematic teaching of the relationship between speech sounds and their corresponding letters or letter combinations. This is known as phonics. For these two areas of phonemes and graphemes, there are learning prerequisites.

With phonemes, students must be able to produce and hear the individual phonemes. For a small percentage of students, recognition, and articulation of phonemes can be challenging and will likely interfere with phonemic awareness development. For multilingual learners, some phonemes that don’t exist in their native language may need to be explicitly taught. For example, in Spanish, there are five vowel sounds, but in English, there are 18 vowel sounds. Some native Spanish-speaking students may need explicit instruction on those vowel sounds that don’t exist in their primary language, especially if they enter school with little exposure to English.

As a basis for understanding the phoneme-grapheme connection (phonics) and using that connection to read words (decode) and spell words (encode), students must first be able to orally blend and segment the sounds in words. This is known as phonemic awareness – the ability to detect, identify, and manipulate the sounds in spoken words. This awareness of phonemes in words is a prerequisite for understanding phonics.

An important note about phonemic awareness and phonics is that instruction should be differentiated. Assessment is key to determine need. For the five percent or so that enter school already reading, assessing their phonemic awareness and phonics skills is important so that they are not getting an inordinate amount of instruction in this area. It is likely, however, that many of these students would benefit from spelling instruction. Equally important to realize is that students who speak another language other than English may already have phonemic awareness developed in their primary language. Phonemic awareness skill transfers so it is not necessary to develop phonemic awareness in English if it already is developed in their primary language. Again, assessment will be key.

Prerequisite learning about graphemes includes students being able to identify and form the individual letters of the alphabet and having internalized the alphabetic principle – that letters and sounds work together to form words. This alphabetic principle, combined with phonemic awareness, are two important insights that students must have in order for phonics to make sense. If phonics doesn’t make sense, they will have difficulty using decoding (or “sounding out”) skills to read and spell words.

Morphemes

Morphemes (the smallest units of meaning). Structured literacy emphasizes teaching meaningful word parts, e.g., prefixes, suffixes, and Greek and Latin roots. Knowledge of these building blocks of meaning form a foundation for decoding, increase reading fluency, and increase the ability for readers to understand the meaning of larger words.

Sentence Structure

Sentence structure (or syntax) addresses word order and grammar of sentences, enabling students to comprehend and construct complex and coherent sentences.

Syllable and Stress Patterns in Longer Words

By teaching syllable division, syllable types, and patterns of stress in words, students advance their decoding and word recognition skills with multisyllabic words.

Orthographic Conventions

Orthography is the writing system of a particular language. English spelling is complex yet is more predictable than most realize. When students (and teachers) realize that the spelling of almost any word can be explained by one or more of the following five principles, spelling accuracy and ability can increase greatly.

- Word’s language of origin and history

- Word’s meaning and part of speech

- Speech sounds are spelled with one or up to four letters, e.g., the long a sound can be spelled with an ā in apron or -eigh in sleigh.

- The spelling of a given sound can change based on its position in the word, e.g., /j/ spelled j in jump or /j/ spelled -dge in badge.

- Spellings are governed by established conventions, e.g., no English word ends in v. An e must be added, e.g., love, give

Vocabulary and Background Knowledge

Structured literacy focuses on the development of vocabulary by way of specific word instruction and word learning strategies (e.g., morphemic analysis), which enable students to expand their understanding of words and their meanings. In addition, background knowledge and vocabulary are inextricably linked. As we learn more about the world through reading and writing and engaging with life experiences, the labels or words that represent that growing knowledge also become more precise and vast. Networks of knowledge are built with vocabulary as the glue to bind these networks together. Simply put, our breadth and depth of knowledge of word meanings increase as our background or world knowledge increases.

Text Structure

Text structure (the specific way text is organized to convey the type of information provided). Teaching the organization of and differences between narrative and informational text and how information is presented in these different structures equips students with the ability to comprehend different types of text effectively. When students are familiar with a particular text structure, “they know what to expect from different parts of the text, where to search for particular types of information, and how the different parts of the text are linked together” (Oakhill, Cain, and Elbro, 2015).

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking requires a complex set of mental activities that, at their core, requires background knowledge. Despite what many think, critical thinking isn’t a set of skills that can be taught (Willingham, 2016). The ability to think critically while reading involves two big ideas.

- make inferences about the text using background knowledge and information read from the text.

- monitor comprehension by knowing when to stop and use fix-up strategies if comprehension is being impaired. This is known as metacognition – thinking about one’s own thinking.

Ultimately, the structured literacy components described above are continually being integrated with authentic reading and writing experiences. An example of this integration occurs during word recognition instruction, where students are not only practice decoding words with an accumulating knowledge of sound-spelling correspondences but they are also taught how to spell words with those same sound-spelling correspondences. In addition, multilingual learners are taught the meanings of the words they are practicing to decode. In language comprehension, students are writing about what they read using the vocabulary, background knowledge, and syntax skills they are learning through instruction and their reading.

Teaching the above components of structured literacy reinforces the reciprocity between language and literacy. Teaching these components provide students with in-depth knowledge about the various layers of language and play a vital role in developing students’ overall language proficiency and literacy skills. The language domains that are emphasized and developed through Structured Literacy include:

- Phonology: The speech sound system

- Morphology: The meaningful part of words

- Syntax: Sentence structure and grammar

- Semantics: The relationships among words and their meanings, and the relationships among sentences and their meanings

- Discourse: The organization of spoken and written communication, e.g., text structure

- Orthography: The written language/how the spelling system works

The various components of the ‘What’ that were described in the previous section can be mapped onto the different language domains above. For instance:

- Phonology and orthography work together to address phonics instruction (phonemes and graphemes – the spellings for those phonemes). Phonemic awareness is related to phonology in that the ability to correctly articulate the phonemes supports the development of phonemic awareness, the ability to hear and manipulate phonemes.

- Morphology relates to identifying and understanding meaningful word parts (morphemes).

- Syntax is related to sentence structure and grammar.

- Semantics is related to vocabulary, background knowledge, and overall reading comprehension, from word-level meaning to sentence-level to passage-level meaning.

- Discourse is related to text structure.

Structured Literacy and the Five Essential Components of Reading

Structured literacy and the language domains it supports also align with the traditional five essential components of reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Although the terminology may differ, structured literacy components incorporate the five essential components within its comprehensive framework.

In other words, the components of instruction that form the ‘What’ of structured literacy can be mapped onto the five essential components of reading, and they can be mapped onto the different language domains. This cross-mapping among the various elements of literacy and language reinforces the idea that structured literacy instructional practices align with the science of reading and are grounded in oral language.

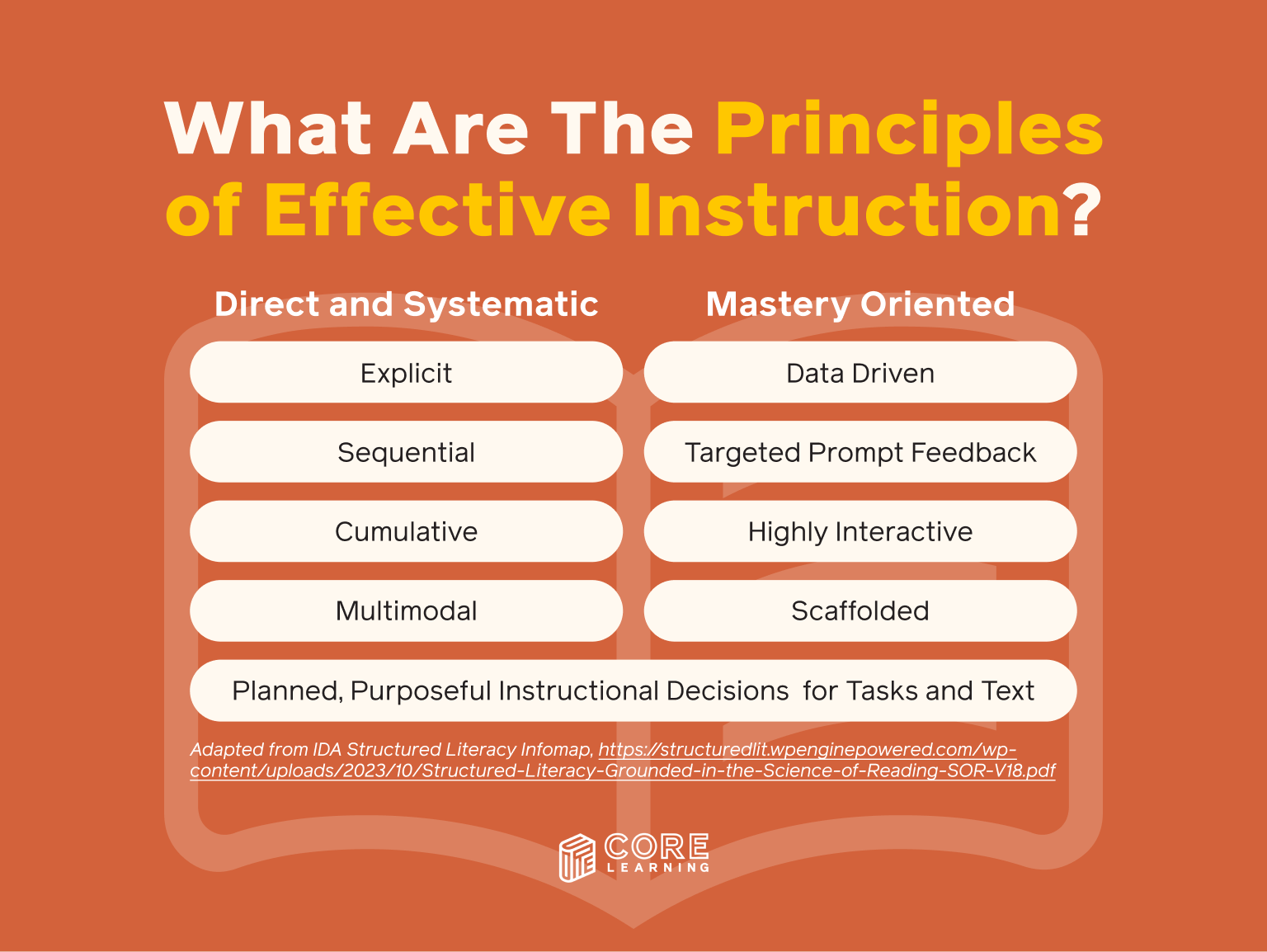

The How of Structured Literacy

Equally as important to the What of Structured Literacy is the How. Structured Literacy incorporates several important instructional delivery and design principles. These principles of effective instruction are:

Explicit Instruction

This method involves clearly and directly teaching students by modeling, explaining, providing guided practice, and supporting independent practice. The process is often summarized as “I do (teacher doing it), we do (doing it together), you do (independent practice).” All skills are directly taught, modeled, and clearly explained. By doing this, explicit instruction ensures students grasp concepts effectively and, with practice, are able to apply the skill or strategy independently and accurately.

Sequential Instruction

With sequential or systematic instruction, a planned sequence to teach skills and concepts progressively is followed. For example, when teaching phoneme-grapheme relationships (phonics) to kindergarteners, start with very simple one-to-one correspondences like in the word cat: ‘c’ spells /k/, ‘a’ spells /a/, and ‘t’ spells /t/. Examples in first grade consist of teaching more complicated spelling patterns, such as the ai spelling for the long a sound in the word rain or the ph spelling for the /f/ in phone. By building upon previously learned skills and concepts, students develop a strong foundation in reading and writing.

Cumulative Learning

As stated above, Instruction follows a planned, logical sequence, from simple to complex, and builds upon previously taught skills. However, this approach also involves consistently reviewing the information that has been previously taught. An example of cumulative instruction is to review previously taught sight words on a daily basis. An additional example occurs when reading decodable text. Reading this special type of text is a cumulative form of practice as it reviews previously taught sound-spelling correspondences in the context of reading connected sentences in narrative or informational text. This instructional design principle acknowledges that learning is cumulative, and students benefit from regularly revisiting and reinforcing previously taught concepts

Multimodal Instruction

Multimodal instruction fosters automatic integration of auditory, visual, and kinesthetic-motor modalities. Having students see, hear, say, and write a word is a broad example of what multimodal instruction entails. Students with language learning difficulties need instruction, which includes demonstration and practice with manipulatives which helps to clarify verbal explanations (Janney & Snell, 2004).

Data Driven

Data-driven teaching focuses on the collection and analysis of data related to student performance and learning outcomes to guide teaching practices. Using the data-driven method, we constantly assess students, either informally by observing them and providing prompt feedback or through regular assessments. If we see that a student is missing some concepts, we can act promptly. See How to Ensure Remote or In-Person Reading Assessments Provide the Data You Need to Guide Instruction.

By employing these teaching methods, we can deliver effective instruction and support students in developing strong reading and writing abilities.

Targeted Prompt Feedback

Prompt feedback in teaching refers to providing immediate and specific feedback to students on their performance or understanding of a concept. It involves offering guidance, corrections, and reinforcement to students in a timely manner.

That said, the feedback is provided in an affirming way and doesn’t single out students. For example, when a student makes an error in a small group or whole group lesson setting, the correction should be made to the entire group so that the student is not singled out. Feedback should be immediate, specific, and concise.

With prompt and affirming feedback, we can identify areas where students are making errors and address them efficiently so that students don’t continue to practice making those errors.. By receiving feedback promptly, students can make corrections and adjustments to their learning so they will practice correctly, leading to improved understanding and skill development.

Highly Interactive

Highly interactive instruction requires students to be active learners instead of passive. Structured literacy requires active student participation through:

- choral response;

- interactive activities that use manipulation of chips or letter tiles to represent abstract ideas like phonemes;

- structured academic discussions about text;

- spelling words with teacher guidance;

- writing in response to reading; and,

- other collaborative learning experiences.

Engaging students in meaningful interactions strengthens their comprehension and language development. Research consistently finds that interactive methods correlate with positive student outcomes, such as higher rates of attention, retention of information, interest in subject matter, and satisfaction (Bligh, 2000; Burrowes, 2003; Sivan et al., 2000).

Scaffolded

A very important technique of instruction is scaffolding – a process of gradually shifting responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student. Scaffolded instruction is a temporary supportive structure that teachers use to help students to accomplish a task that they could not complete alone. There are many types of scaffolding examples. One example highlighted on pages 181-182 in the Teaching Reading Sourcebook is where blending routines are described. In this example, sound-by-sound blending and continuous blending are both considered heavily scaffolded instructional routines. Either would be used as students are first learning the blending routine to “sound out” or decode words.

However, as students become more familiar with blending and continue to learn more sound-spelling correspondences, teachers can move to a less scaffolded blending routine called whole-word blending. This routine provides less support and requires more effort on the students’ part to decode the words. An important caveat is that even though students may have become more familiar with blending when new sound-spelling correspondences are introduced, it is important to start the blending instruction with a few words using either of the two aforementioned heavily scaffolded routines. Once the teacher sees that most students are easily blending words with the new sound spelling, the teacher can move to whole-word blending. Spelling-focused blending is even less scaffolded by calling attention to the vowel sound-spelling, and then students just read the word.

Which Teachers Should Use Structured Literacy?

Structured literacy is a versatile approach that can benefit teachers across all tiers of instruction. Its systematic and research-based framework makes it suitable for addressing the diverse learning needs of students.

- Tier 1 instruction involves general classroom instruction, where teachers work with all students in a typical classroom setting. This encompasses the core curriculum and addresses the educational needs of the majority of students.

- Tier 2 instruction focuses on providing targeted interventions to students who require additional support or who are at risk of falling behind. These interventions are designed to supplement Tier 1 instruction and provide more personalized assistance.

- Tier 3 instruction is highly individualized and intensive, targeting students who require intensive interventions due to significant learning difficulties or differences. These interventions are tailored to meet specific student needs and may involve specialized programs or services. Neither Tier 2 or Tier 3 instruction replaces Tier 1 instruction.

Improving Student Outcomes With Structured Literacy

Structured literacy is an invaluable approach that benefits all students. Thanks to this universal applicability, as well as its emphasis on systematic and explicit teaching of literacy and language skills, structured literacy equips students with the tools they need to become confident and proficient readers and writers.

For further exploration and implementation of structured literacy practices, educators can turn to CORE Learning’s Teaching Reading Sourcebook. This comprehensive reference book, rated exemplary by the NCTQ in its alignment to and coverage of the five essential components of reading, is organized around the elements of explicit instruction, answering the what, why, when, and how of teaching reading. It provides access to knowledge that’s grounded in research-informed and evidence-based practices with practical sample lesson models for teachers to apply in their classrooms.

Download sample pages of the Teaching Reading Sourcebook here.